There are two ways to live: you can live as if nothing is a miracle, or you can live as if everything is a miracle.

More than any other yoga practitioner, Iyengar was responsible for the spread of interest in yoga in the west over the last half-century, having originally introduced the violinist Yehudi Menuhin to the art in the early 1950s.

Iyengar used to say “my body is my temple and asanas are my prayers”, living up to that maxim, keeping himself supremely fit. Yet during his childhood he was, in his words, “a creature of contempt for my people” because of his constant ill-health. Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja (BKS) Iyengar was born into a family of 13 children, only 10 of whom survived. His father came from the village of Bellur, in the southern Indian state of Karnataka. Iyengar retained his ties with that village and later established education, public health and other social projects there. When Iyengar was five, his father left the village and his job as a primary school headteacher, moving to Bangalore, where he worked as a clerk.

Iyengar was introduced to yoga by one of his brothers-in-law, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who ran a yoga school supported by the maharaja of the southern princely state of Mysore, and when Iyengar was 19 sent him to Pune. That city was to become his home for the rest of his life, but his early days there were not auspicious. He was employed by the Deccan Gymkhana Club. The staff there were jealous of his success and one night burned all his equipment. After three years, the club asked Iyengar to leave. Sometimes he could only afford a plate of rice every two or three days. But gradually he came to be better known and more secure.

The break that transformed Iyengar from a comparatively obscure Indian yoga teacher into an international guru came in 1952, when Menuhin visited India. Because Iyengar had taught the famous philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, he was asked to go to Bombay to meet Menuhin, who was known to be interested in yoga. Menuhin said he was very tired and could spare only five minutes. Iyengar told him to adopt a relaxing asana, and he fell asleep. After one hour, Menuhin woke refreshed and spent another two hours with Iyengar. Menuhin came to believe that practising yoga improved his playing, and in 1954 invited Iyengar to Switzerland. At the end of that visit, he presented his yoga teacher with a watch on the back of which was inscribed, “To my best violin teacher, BKS Iyengar”.

From then on Iyengar visited the west regularly, and schools teaching his system of yoga sprang up all over the world. There are now hundreds of Iyengar yoga centres. During his early travels, he had to face misunderstanding and racism. British immigration officers thought he was some sort of magician and asked him whether he could walk on fire, chew glass or swallow razor blades. A London hotel once refused to accept him as a guest until Menuhin intervened. Even then, Iyengar was told he could not eat in the dining room, and his meals were sent to his room.

Iyengar always insisted that yoga is a spiritual discipline, describing it as “the quest of the soul for the spark of divinity within us”. He used to tell his pupils to “be aware that the current of spiritual awareness has to flow in each movement and in each action”. As to its wider benefits, he maintained: “Before peace between the nations we have to find peace inside that small nation which is our own being”. He regarded much of the yoga that became popular in the west as “nothing more than physical exercise”. Unlike western keep-fit exercises, he insisted, yoga must not put any strain on the heart.

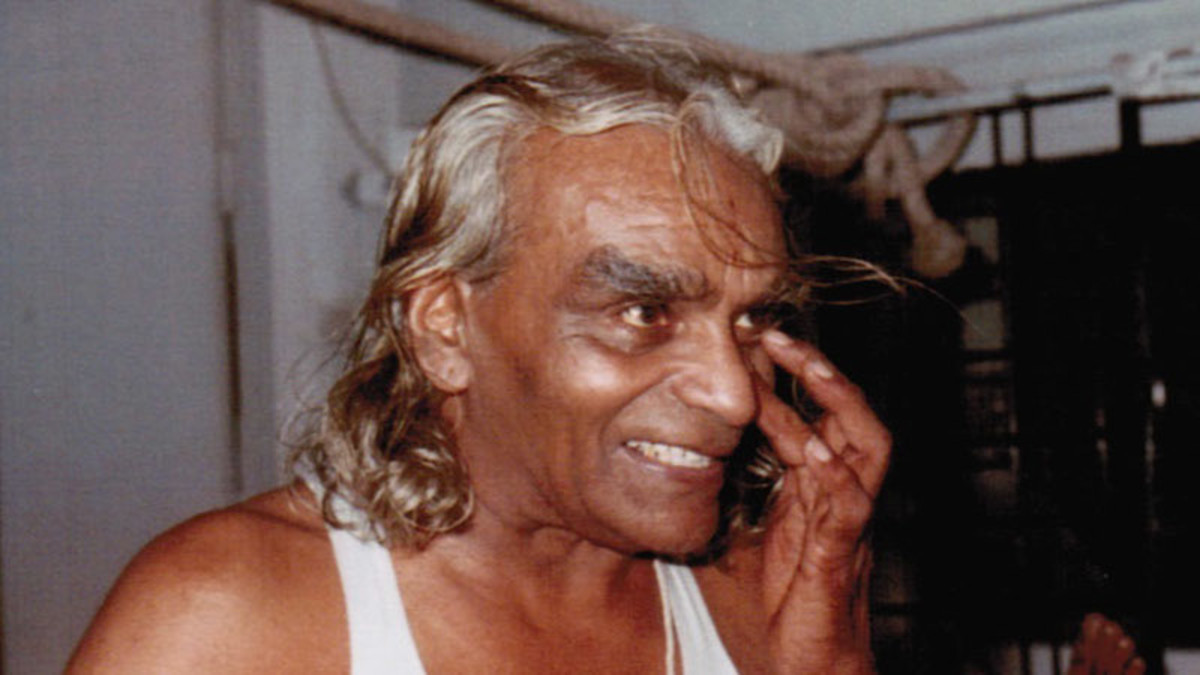

Iyengar appeared daunting with his leonine head, mane of hair and formidable eyebrows, which, as he used to say, went in two directions. He had a reputation as a stern teacher, and would insist on his pupils copying his asanas with absolute accuracy, achieving perfect balance. But he also patiently helped those who were having difficulty with their asanas and designed special exercises and equipment for pupils with physical problems. He studied anatomy, psychology and physiology to pioneer modern therapeutic yoga.

He cured one of his pupils, Nivedita Joshi, from a slipped-disc condition that had left her unable to move her hands and legs; she now runs the Iyengar centre in New Delhi. But Iyengar never sought publicity for his achievements and lived a simple life, unmoved by his international renown. Earlier this year he was awarded a state honour, the Padma Vibhushan.

Iyengar’s marriage to Ramamani was arranged by his family, and was very happy. He said: “We lived without conflict as if our two souls were one.” She died when she was 46 and Iyengar called his yoga school in Pune after her. His son, Prashant, and daughter, Geeta, are now the principal teachers in the Pune yoga school, and his granddaughter, Abhijat, has also taught there. He is also survived by four other daughters.

Family Stricken by Influenza Epidemic

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar was a native of the southern Indian state of Karnataka, born on December 14, 1918, in the midst of the worldwide influenza epidemic of that year. He was the 11th of 13 children, ten of whom survived. Iyengar spent his early life in a village called Bellur, which has been reported as his birthplace, but he told Contemporary Authors that he was born in the larger city of Bangalore in the same region, where the family later moved. Iyengar’s family was part of the high-status Brahmin caste, and the name Iyengar is associated with the family’s membership in a group of South Indian adherents of a specific philosophical branch of Hinduism. Iyengar’s father, Bellur Krishnamachar Iyengar, was a schoolmaster in a nearby village, and the family raised crops on a small plot of land they had inherited.

Iyengar’s mother, Seshamma, was stricken with influenza during the pregnancy that culminated in his birth, and Iyengar suffered from health problems that would plague him for much of his childhood. At first he was not expected to survive. He was prone to the diseases endemic to the area and suffered multiple bouts of typhoid, malaria, and tuberculosis. “My poor health was matched, as it often is when one is sick, by my poor mood,” Iyengar wrote in his book Light on Life . “A deep melancholy overtook me, and at times I asked myself whether life was worth the trouble of living.”

Iyengar’s situation was worsened by the death of his father from untreated appendicitis when Iyengar was nine. The young boy did poorly in school and he failed a key English-language examination. The exam result brought his schooling to an end, and Iyengar’s family began to wonder how the still frail young man might make a living. Iyengar’s brother-in-law, Shriman Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, worked as a yoga teacher and scholar in the employ of an Indian noble family in the city of Mysore, and in 1934 Krishnamacharya, who helped create the now widely practiced hatha yoga style, invited Iyengar to move temporarily to Mysore to look after the family while he was away conducting yoga classes in other parts of the region.

Iyengar stayed on in Mysore and took yoga lessons from Krishnamacharya. At first he was, he told Colleen O’Connor of the Denver Post , “an anti-advertisement for yoga.” Leaning forward, he could barely touch his knees, much less his feet. Krishnamacharya’s harsh teaching regime did not endear him to his students, who often sneaked away from their classes, and Iyengar at first was as unenthusiastic as the others. At one point Krishamacharya forced him to do a split-leg exercise for which he was unprepared, and he tore a ligament and was unable to walk for some time. But Iyengar noticed that, for the first time in his life, he was growing stronger, and he persisted in his training. One of Krishnamacharya’s top students disappeared just days before the royalty of the area were due in Mysore for an important yoga demonstration, and Iyengar was tapped as a replacement. He did so well that he was able to join his teacher on the road for other classes and demonstrations.

Began Teaching All-Female Class

On one of these tours, a group of women became fascinated with the art of yoga and asked for lessons. Iyengar was chosen to be their teacher because, at 18, he was Krishnamacharya’s youngest disciple, and it was thought to be less improper for the women to be taught by a man who had not yet reached full adulthood. Iyengar did well at this assignment and was sent on to a bigger one: Krishnamac-harya named him to fill a teaching post at the Deccan Gymkhana Club, an upper class sports club in the city of Pune, in India’s Maharashtra state.

Here, once again, Iyengar felt at a disadvantage in many ways. He spoke English badly and the local language, Marathi, not at all (the language of his native Karnataka was Kannada). The yoga students at the Gymkhana were older than Iyengar and in better condition, sometimes more advanced in yoga than he was. Iyengar, fearful of having to return in disgrace to his fearsome teacher in Mysore, embarked on a regime of practice that could last up to ten hours a day. His aim was to become a total yoga expert, fully systematizing the diverse bits of knowledge his teacher had passed on, and getting to know the ultimate potentialities of his own body. Neighbors in Pune, most of them still unfamiliar with yoga, questioned his sanity, but Iyengar’s knowledge and strength deepened. It was during this period that the systematic discipline later known as Iyengar Yoga was developed.

As Iyengar’s studies began to bear fruit, the Gymkhana extended his original six-month contract to three years. After this term ended, Iyengar launched a career as an independent yoga teacher. At first he had few pupils, and there were days on which he subsisted on little more than rice and tea. Nothing would dissuade him, however, from his hours of daily practice. Iyengar’s family, anxious to see him in a more settled existence, arranged his marriage to a 16-year-old girl named Ramamani. At first he refused to do more than meet her briefly, but the relationship flowered into marriage on July 13, 1943. Ramamani became a strong backer of Iyengar’s enthusiasm for yoga, and the marriage was a long and happy one that produced six children.

Several facets of Iyengar’s yoga teaching set him apart from other gurus. He believed that yoga was not a practice to be restricted to specialists but could benefit anyone, and he began to incorporate aids such as ropes, belts, and blocks into yoga routines for those who needed them. Many elderly people over the years would flock to Iyengar’s classes and accomplish feats of which they would not have believed themselves capable. Iyengar was also living testimony to the idea that yoga could aid in the solution of even serious health problems, and tales of miraculous cures began to accumulate around him. Iyengar began to attract famous Indians as students, including the philosopher J. Krishnamurti and the cardiologist Rustom Jal Vakil.

Taught Yoga to Famed Violinist

It was Vakil’s wife who introduced Iyengar to one of his most renowned students, star American classical violinist Yehudi Menuhin. An initial five-minute meeting between the two men in 1952, arranged while Menuhin was on a concert tour in India and expressed an interest in yoga, ballooned into a session lasting several hours. Iyengar and Menuhin became friends, and Menuhin touted the improvement in his violin playing that he said had come about after he began practicing yoga. When Menuhin returned to India in 1954, he suggested that Iyengar return to the West with him and give yoga lessons in Europe and the United States.

The result was a publicity bonanza, for Menuhin’s friends and acquaintances were a highly visible group. Iyengar taught Elisabeth, the octogenarian Queen of Belgium, to stand on her head, and he did a yoga demonstration for the Soviet Union’s Premier, Nikita Khrushchev. At the invitation of Standard Oil heiress Rebekah Harkness, he came to the United States in 1956. American interest in yoga was growing—indeed, Indian gurus were already active there—but Iyengar was repelled by the country’s materialism. “I saw Americans were interested in the three W’s—wealth, women, and wine,” he told O’Connor. “I was taken aback to see how the way of life here conflicted with my own country. I thought twice about coming back.” Iyengar lived for a time in Switzerland and did not return to the United States until the early 1970s.

By that time, however, he had become a well-known author, in America as well as the rest of the world. Frustrated by existing yoga manuals, which he felt cheated the user by giving directions that were inadequate for the realization of the poses depicted in photographs, he wrote Light on Yoga in 1966. Iyengar worked closely with a photographer on 4,000 shots of himself in yoga poses or asanas, from which the final images in the book were selected. Four decades later, Light on Yoga was considered the preeminent yoga text in the field, with new translations into other languages appearing regularly; it was often referred to as the bible of yoga.

Light on Yoga spawned a large group of Iyengar followers who wanted to disseminate Iyengar’s ideas in a systematic way. The popularity of yoga continued to rise in the United States with the debut of the Public Broadcasting System television program Lilias! Yoga and You in 1972, and the following year the first Iyengar Yoga studio opened in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Iyengar himself made a return visit to the United States in 1973, and by 1984 the first annual International Iyengar Convention, held in San Francisco, drew a crowd of 800 devotees. Iyengar’s followers, who referred to him as Guruji, generally maintained their adherence, despite his habit of physically slapping students who made errors; some complained (according to O’Connor) that his initials, B.K.S., could stand for “beat, kick, slap.”

Iyengar divided his time between India and the West over the later decades of his life. In 1975 he established the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute in Pune, named after his late wife; the institute became a key center for the training of new Iyengar instructors. Working, as he had on Light on Yoga , with native speakers of English as co-authors, he wrote seven more books, including Body the Shrine, Yoga Thy Light (1978), The Art of Yoga (1985), The Tree of Yoga (1988), Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health (2001), and Light on Life , (2005), in which he interwove practical yoga advice, philosophical reflections, and stories from his own life and career.

Gradually retiring from teaching, Iyengar was supplanted as guru by two of his children, daughter Geeta and son Prashant. He continued, however, to practice yoga on a daily basis, and well into his ninth decade he was able to stand on his head and stay in that position for half an hour. In 2005 Iyengar made a tour of the United States in order to promote Light on Life , for which he had reportedly received a seven-figure advance. (He plowed the profits from his books back into his institute and into local development projects in Bellur.) By that time, Iyengar counted Hollywood celebrities, including the lithe Seinfeld actor Michael Richards and actress Annette Bening, among his followers, and Iyengar Yoga schools were operating in well over 250 cities. “I am leaving everything for posterity, as a guide for generations to come,” he told Hilary de Vries of the New York Times . “If they read my books, their confidence will grow so that none can shake them.”

Oops, you didn’t enter anything. Try again or contact us